#SimBlog: Disabled Child with Complex Comorbidities

☎️ “Paediatric RED CALL 5 minutes, ?18 y/o male, tonic clonic seizure >20 minutes. Unresponsive. Known cerebral palsy and epilepsy”

RR 15 breaths/min, Saturations 88% (in air), HR 110 bpm, Temp 39°C, CRT 3 seconds, Blood pressure 110/70 mmHg

The Scenario

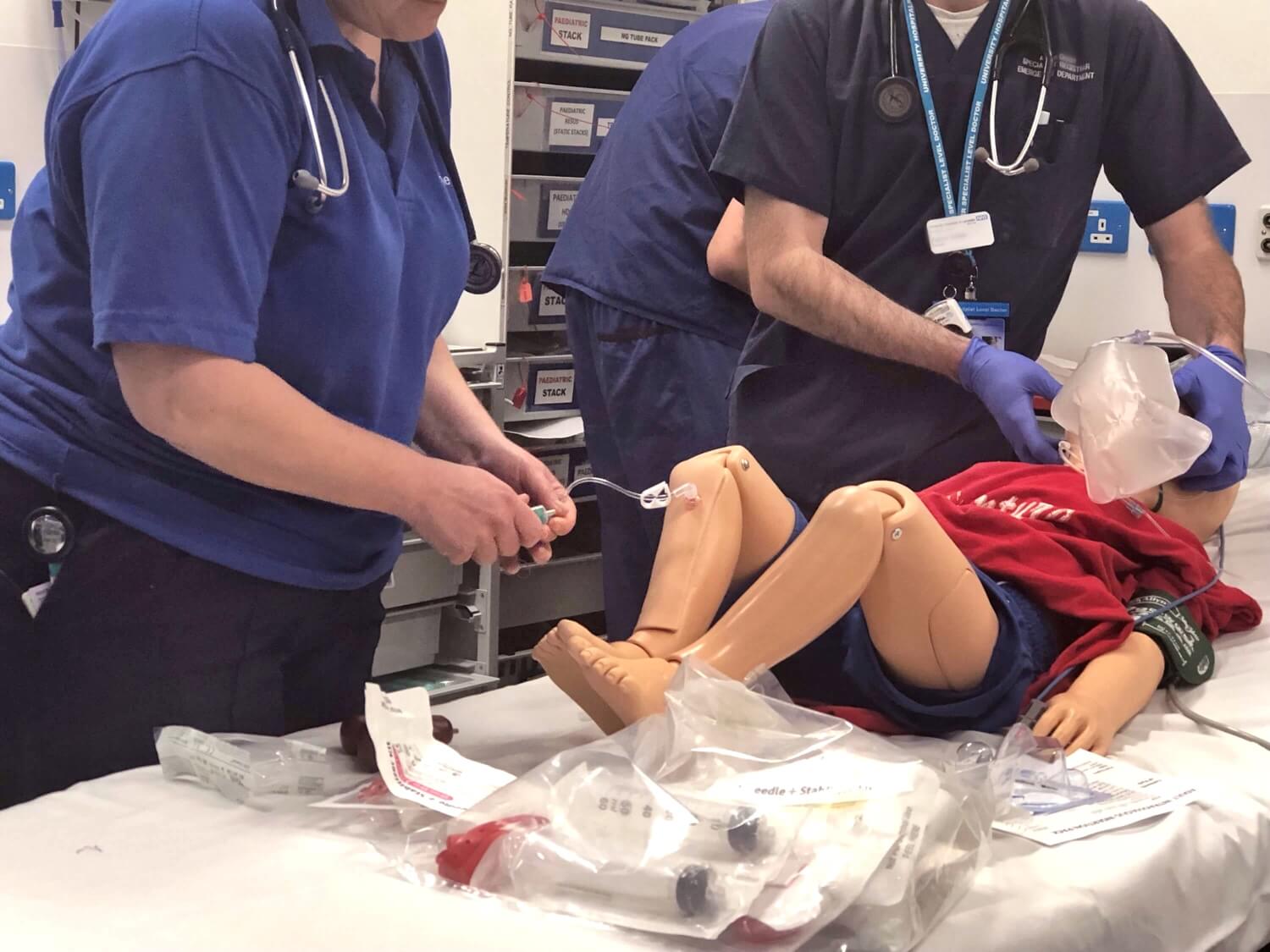

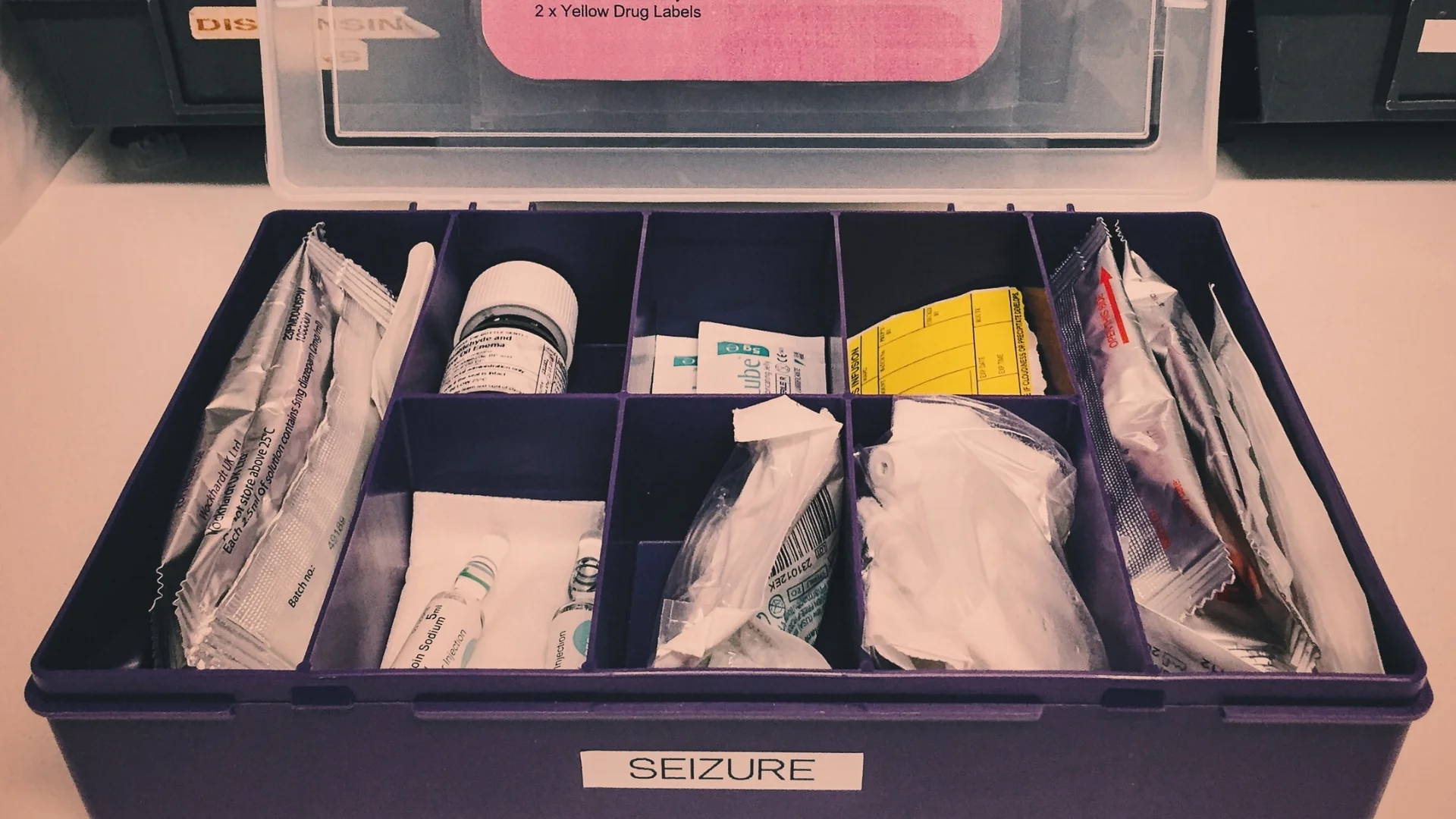

Whilst the “child” is eighteen, the resuscitation lead has requested a paediatrician as the young male is still in transition to adult services. With not a minute to spare, the adult nurses, led by a paediatric junior doctor, calculate the WETFLAG. They grab the seizure grab box and begin preparing equipment. The team members (having not worked together before) quickly introduce themselves and assign roles, just as the paramedic arrives…

Additional history from handover

Unwell for two days, high fever, less active, mild cough

This morning: tonic clonic seizure with copious secretions

Family administered buccal midazolam, paramedics have given rectal diazepam

Total seizure duration at arrival = 30 minutes

Oxygen delivered, suctioning provided, known difficult airway and previous ITU admissions

A Guedel airway is inserted and 15L/min oxygen is administered with monitoring. The patient remains unresponsive and fitting but appears to be pink and breathing. Secretions are notable and suctioning is nearly continuous.

“Shall I give rectal diazepam?” … “We need IV access!”

Our intrepid team leader pauses…

“No, he’s had two benzos prehospital, but we do need IV access. I’m also worried about the airway, please fast bleep the paediatric anaesthetist to the ER.”

The primary survey reaches circulation: identifying a stridorous airway with copious secretion, bilateral widespread crackles on the chest and cool peripheries with capillary refill of 3 seconds. At this point the paediatric emergency registrar arrives to assist. ABCDE is repeated, a nasopharyngeal airway is inserted with improved saturations resulting, IV access has failed. Then “some kind of central line” is found alongside a presumed gastrostomy. A capillary blood sugar tests low (2.4), and someone overhears that the parents are on their way.

A plan forms and is announced…

“Right, we’ve stabilised the airway and breathing and are expecting anaesthetic support shortly. We need to address the poor perfusion, the low blood sugar and in view of the continued fitting we need to prioritise IV phenytoin. We also need bloods, blood cultures and to administer IV Ceftriaxone to cover for sepsis.”

Conversation follows…

“What weight are we using? He doesn’t look that big!” … “The central line is not flushing.” … “What about IO access?” … “What about his temperature?”

IO access is agreed and quickly achieved. Moments later 5ml/kg 10% dextrose is given, followed by 20ml/kg 0.9% Sodium Chloride. At this point the phenytoin is ready and commenced when the anaesthetist walks in…

The Debrief

Lots to talk about, but in the privacy of the debrief room emotional offloading is the important first step. Lots of cognitive challenges, lots of situational stress, lots of unexpected challenges. None the less the team’s spirits are high and it’s not long before we get down to business discussing the learning outcomes from the session.

Learning Outcomes

Weight – remember to think twice

The disabled child – expect the unexpected

The difficult resuscitation – stand at the end of the bed and take a breath

1) Weight (remember to think twice)

When an unwell child turns up needing resuscitation – weight might be the last thing on your mind. Yet it impacts everything that follows, from airway equipment sizes… to fluid calculations… to drug doses. We’re not expected to guess. Instead we can ask the parents if they know a recent weight from clinic. We can utilise tools (e.g. formulae, Broselow tape). We can even (if they’re not too unwell) get them onto the scales.

Whatever you do, remember to think twice and just do a mental double check that the weight you’re using looks right. In this scenario our patient with cerebral palsy barely weighed 20 kilograms, nowhere near the >50kg estimated for his age!

And another thing – above 12 years of age the formulae become increasingly useless.

Further Reading

Don't Forget the Bubbles: I can guess your weight

2) The Disabled Child (expect the unexpected)

1-in-20 children in the UK have a significant disability. When unwell, there is often heightened anxiety, uncertainty and stress. No, not from the parents. From us! Children with disabilities undoubtedly require more concentration of our skills and attention to avoid serious illness being missed.

Furthermore, families who’s children have chronic illness often avoid hospital at all costs. As a result they may therefore present later in their illness. So you better pay attention!

Still stuck? Ask the parent what do they think? What do they know? Do they have a recent clinic letter? The parents of a child with disability are often your best ally in these situations. They know whether the “breathing difficulty” or “conscious level” is normal for their child. They are experts. Ignore them at your peril.

Further Reading

RCPCH: Children and young people with complex medical needs (PDF)

3) The Difficult Resuscitation (stand at the end of the bed and take a breath)

Clearly defining yourself as the leader is not just important for you (getting into the right headspace) but it is essential for your team. If you are the leader, you as the ‘sinus node’ pacemaker for the whole resuscitation. That’s not to say information can’t flow both ways of course.

Getting hands-on may be necessary, but tap yourself on the shoulder when you start to stray away from the end of the bed. Keep your helicopter overview (your situational awareness) and see your complex resuscitation scenarios soar to success!

Further Reading

Resuscitation Team Organization for Emergency Departments: A Conceptual Review and Discussion by L.B. Mellick and B.D. Adams

Procedures

1) Intraosseous Access (how soon is too soon?)

Life threatening situation, need for life saving drugs, failed cannulation attempts? Don’t delay! Say it, Get it, Do it! The decision to use intraosseous access shouldn’t be taken lightly but far too often it’s use is delayed for non-clinical reasons. As previously discussed, they can be life-saving. See our forthcoming video on how to insert an IO and be an IO champion!

2) Airway Adjuncts (how, when and why?)

Neurodisability and acute respiratory tract infections never mix well. Such vulnerable airways, with or without a seizure, often require airway adjuncts. Here we were told by the paramedic that the child had a previous difficult airway – we presume therefore they were difficult to intubate. Hence in or scenario, anaesthetic help was called early.

Furthermore, both an oropharyngeal and later a nasopharyngeal airway were used to good effect allowing a more patent airway with an improved ability to suction excess secretions. The child’s oxygenation improved whilst the work of breathing was massively improved. Let’s quickly review the basics of sizing…

3) Central Lines & Gastrostomy Tubes (friend or foe?)

In our scenario, a PICC line and gastrostomy tube became visible on full exposure of the patient. In a child with complex disability – look for them. They may be a site of infection; the cause of the presentation (e.g. blockage); or a route of enteral/intravenous access.

Some children with chronic illness have had a lifetime of venous cannulation so expect finding a vein to be hard. A PICC line (if used correctly and not blocked) can provide a route for resuscitative intravenous drugs. The gastrostomy can provide a route of enteral drugs (and fluid) without compromising the airway. Both can be your friend in a resuscitation. They can also be your foe, so don’t spend too long relying on them in an acute situation.

If in doubt – think of your plan B and C early, as in our scenario time can be inadvertently be wasted using devices with which you’re not familiar. Again, a family member (if available) can be your ally here.

Further Reading

Great Ormond Street (NHS): Central venous access devices (long term) & Gastrostomy management

In Summary

Don’t be perturbed by the child with complex comorbidity. Go back to basics – ABCDE. Take a breath. Speak to parents (if available). Be positive. But always assume something serious may be going on, rather than the other way around.