#SimBlog: A Paediatric Stabbing

The Scenario

“A large (muscular) 15-year-old adolescent (played by yours truly) is walked in by hospital security clutching a blood-soaked sheet with a knife sticking out his right leg.”

As we enter Paediatric Majors (parents and staff aghast) I’m helped onto a trolley and wheeled into Resus. *DING DONG* “Paediatric crash call, Resus bay” goes the tannoy system. The team assemble.

Our CT3 ED doctor took the helm and performs a primary survey:

<C> No sign of catastrophic haemorrhage

A: No C-spine concerns, groaning in pain

B: No wounds/injuries to chest, saturating 100%, equal air entry, slight tachypnoea 35/min

C: Tachycardia at 100 breast per minute, hypertensive 150/60mmHg, CRT 2s centrally, pink right foot, CRT 3s

D: GCS 15/15, initially alert but becoming confused, no signs of head injury

E: Knife sticking out lateral right thigh, no visible bleeding or oozing, no haematoma felt, temperature 36.0°C. Full top-to-toe performed. Underside of patient yet to be examined.

With security in the background, whilst also surrounded by medical staff, I start to feel more unwell and struggle to answer the doctors questions. The pain is making me sweaty and I almost throw up (those acting lessons pay for themselves).

“Give oxygen 15L/min non-rebreathe mask. Two wide bore IV cannulas please. Remember group and save! What’s the blood gas? Put out a major haemorrhage call and a trauma call.”

“Shall we give fluids?” “No, let’s give tranexamic acid, and prepare blood.”

“M, can you team lead… I’m going to reassess an A to E. We also need to check underneath him for injuries.”

Further help arrives in the form of a paediatric surgical SpR, a porter, a radiographer, nurse in charge, doctor in charge etc. Helpfully, the sliding glass bay doors assist with crowd control. A handover is given and just as the surgeon begins to reassess… the simulation is over. Everyone is invited into the room. It’s time to discuss!

The Debrief

This simulation drew departmental attention. With participants and observers gathered we began to revisit the scenario, being careful to be sensitive to people’s needs.

The context

Sadly paediatric stabbings are on the rise. Notoriously, London is seeing record numbers. Statistics there suggest victims are male (97%) coming from deprived areas (73%) with most stabbings occurring after school (4pm-6pm) minutes away from their homes (within 5km) (Vulliamy et al. 2018). Here in Leicester too we regretfully are seeing cases. As a paediatric doctor, honestly, I would have had no clue what to do! Indeed, this brings us to the first of our learning objectives…

Further Reading

Vulliamy P, Faulkner M, Kirkwood G, et al. Temporal and geographic patterns of stab injuries in young people: a retrospective cohort study from a UK major trauma centre, BMJ Open 2018;8:e023114

Learning Objectives

1) Call for help, “I need an adult!”

It is never wrong to call for help. In this case, a trauma call is warranted. Consider the major haemorrhage protocol. Finally, in my view, utilise your adult emergency colleagues. You might be the best paediatric doctor in the world, but believe me they’ll have seen more stabbings than you!

2) Turn off the tap!

In our case, we had a penetrating wound to the lateral thigh with a knife in situ. The team applied pressure to the area – importantly not removing the knife. There was no active bleeding and no haematoma identified. But… what if it began to haemorrhage?

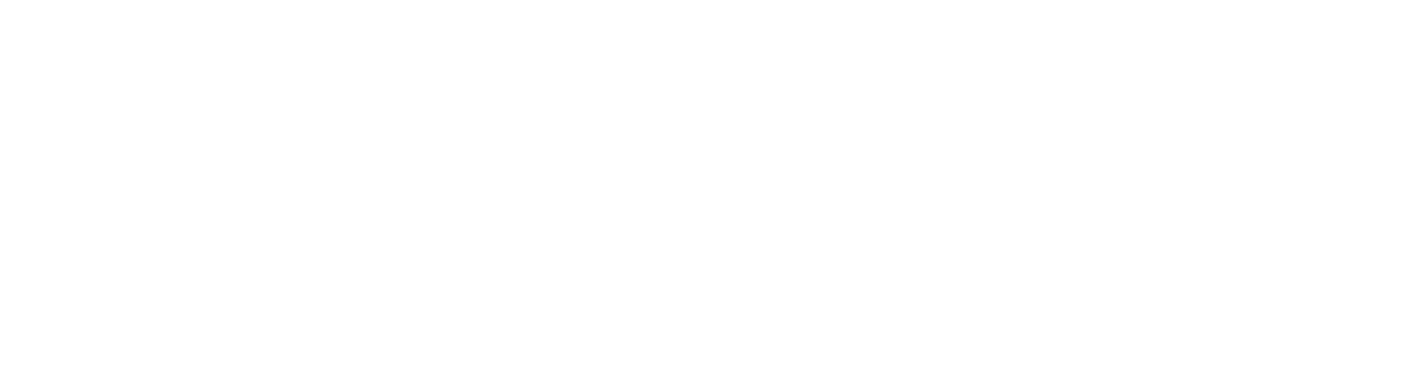

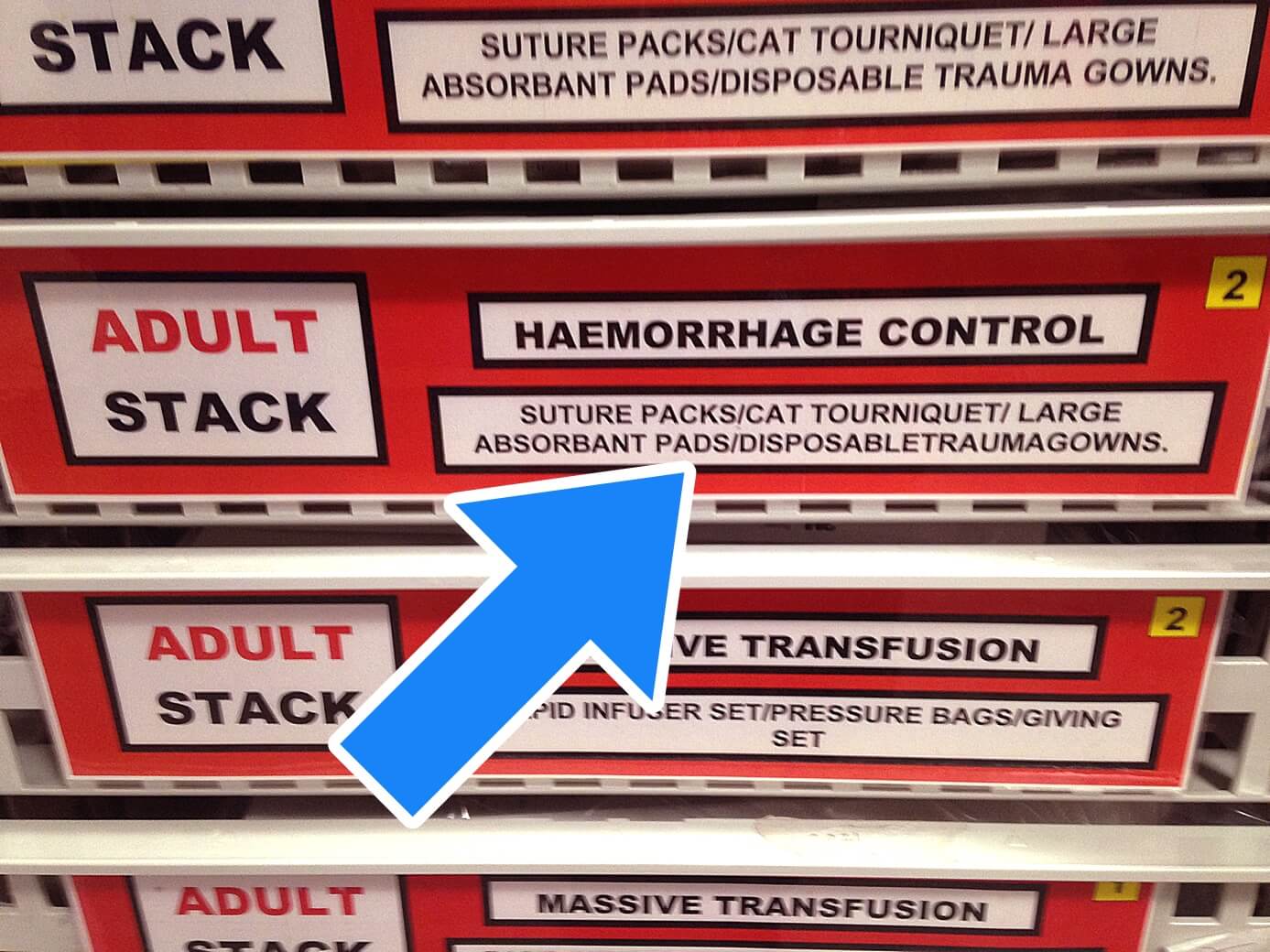

In addition to <C>ABC management grab your haemorrhage control kit! You’ll have pads, bandages, sutures and ‘magic’ QuikClot® sponges that are impregnated with kaolin (a mineral that accelerates the clotting cascade). These are good for your surface bleeds but can sometimes help temporarily even for more severe bleeds.

Then there’s the CAT tourniquet, for severe bleeding when seconds count. All efforts should be made to stabilise the patient before moving, but remember getting the surgeons early in case they’re the only people who can stop the bleed!

3) Giving the right treatment

For a full discussion of major haemorrhage, see resource below. In our simulation there were a number of important points…

Do we give fluid? In short, no. Crystalloid could exacerbate the bleed, worsen the acidosis (which inhibits coagulation), dilute the clotting factors, dilute the haematocrit and overall just makes things go from bad to worse. So in short, replace blood with blood products. “The ideal ratio of blood products is debatable. An aggressive approach such as 2:1:1 Packed Red Blood Cells: Fresh Frozen Plasma: Platelets has been suggested to improve survival.”

Further Reading

- Don't Forget the Bubbles: Stabbings in Kids – When and Where?

- RCEM Learning: Managing Major Haemorrhage in the Emergency Department

- JPAC: Transfusion Management of Major Haemorrhage

What about tranexamic acid? In short, yes. The CRASH-2 study, though performed in adults, suggests TXA can be used safely. If used it must be within 3 hours, and though there is uncertainty of benefit, there are no side effects. So in short, give it!

Further Reading

The Lancet: CRASH-2: Tranexamic Acid and Trauma Patients

And finally…

What about pain relief? Whilst analgesia may not be top of your list of priorities, judicious titrated amounts of intravenous morphine for the child who is haemodynamically stable can be vitally helpful. Not only is it kind but it can pay dividends in helping ongoing assessments (with the physiological effects of pain subtracted).

4) Where next?

At the end of our simulation, the main question was “where next?” Does this child go to the CT scanner? What about theatre? What about transfer to a major trauma centre? “Where next” should be in your mind from the start. In our scenario the child was haemodynamically stable with trauma to an extremity. The knife was in the lateral thigh (low risk) and the knife was still in place. This “where next” question needs a multidisciplinary answer between surgeons, interventional radiology and your resus team. Ask it early! Certainly in our case this child didn’t need transfer and was likely looking at theatre to have the knife removed.

Remember: LEAVE THE KNIFE ALONE.

Approaching a Paediatric Stabbing

The following is taken from Tessa Davis’ excellent tweet on how to approach paediatric stabbing. I’m not going to re-invent the wheel, but I hope you like my infographic!

Put out a trauma call: get help from the people in your hospital who are around and can help.

Do a stab check: check the back, axillae, groin, perineum, and buttocks. These are easy places to miss (your patient might not even know they are there). Don’t miss a second, more serious injury.

Do a good primary survey: is it a peripheral or central wound?

Peripheral wounds: If they have a single wound in their leg, think about whether it needs imaging. Do they have active bleeding (have they hit a vessel)? Do they have concealed bleeding (i.e. a haematoma)? Are they neurovascularly intact? Get a CT angiogram if you’re not sure.

Central wounds: If they have a central wound then treat it as an emergency, even if you’re not sure. Look for the injuries they might have. Chest wound? Tamponade, haemothorax, pneumothorax, flail chest, diaphragm laceration. Abdo? Liver, spleen, kidney, bowel lac. Get imaging for central knife wounds. A FAST scan doesn’t rule out an injury. Get a CT.Tranexamic acid: no evidence in stabbings specifically or in children. But minimal side effects.

Do a venous blood gas: in healthy patients they can compensate well. A VBG can give you a clue as to whether there’s a problem.

Who do you call? Speak to your major trauma centre for advice. But most haemodynamically stable patients can be managed in a trauma unit, not an MTC. If they are unstable then ask your own surgeons to review to see whether they can transfer or need to take to theatre here. But your real value and opportunity comes in sharing information – with police, safeguarding, and social services. Through sharing data, we can target the reduction of knife injuries. Your ED should have a lead for sharing this data.

Be compassionate! You might be the only healthcare professional your patient ever sees. Talk to them, ask them about their life. As them about their hopes, dreams, and what makes them feel safe. Aim for a connection at that moment. You don’t need to be a trauma guru, just be a human being.

Recommended Reading

- Apps, John R et al. Stabbing and safeguarding in children and young people: a Pan-London service evaluation and audit. JRSM short reports vol. 4,7 1-7. 5 Jun. 2013

- General Medical Council. Confidentiality: good practice in handling patient information.

- Van Waes, Oscar J F et al. Treatment of penetrating trauma of the extremities: ten years’ experience at a dutch level 1 trauma center. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine vol. 21 2. 14 Jan. 2013

- Anderson, Robert J. et al. Penetrating extremity trauma: identification of patients at high-risk requiring arteriography. Journal of Vascular Surgery, Volume 11, Issue 4, 544 - 548

- RCPCH, Evidence Statement: Major trauma and the use of tranexamic acid in children, November 2012

- Urban D, Dehaeck R, Lorenzetti D, et al. Safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid in bleeding paediatric trauma patients: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012947

- S Blain, N Paterson. Paediatric massive transfusion. BJA Education, Volume 16, Issue 8, 1 August 2016, Pages 269–275