#SimBlog: If You Focus On The Problem...

“The 1st infant is a 4-month-old ex-preterm with a 2-day history of cough and coryzal symptoms. Today has vomited after each breast feed and has developed difficulty with his breathing.

~

The 2nd infant is 6-week-old and has exactly the same presenting symptoms…”

Case 1: Observations

A – Patent

B – RR 60, sats 89% in air, recessions noted

C – HR 180, CRT < 2 sec, BP 90/50

D – Alert, BM 6

E – Temp 37°C

Clinical Findings

Fine scattered crepitations heard throughout lung fields

Normal heart sounds, femoral pulses well felt

No hepatomegaly

Case 2: Observations

A – Patent

B – RR 60, sats 99% in air, recessions noted

C – HR 165, CRT < 2 sec, BP 90/50

D – Alert, BM 6

E – Temp 37°C

Clinical Findings

Crepitations heard over both lung bases

Pan systolic murmur heard, femoral pulses well felt

3 cm hepatomegaly palpable

Case 1: Why We Simulated?

Bronchiolitis is a common lower respiratory tract infection, affecting babies and children less than 2 years old. Around one in three children in the UK will develop bronchiolitis during their first year of life. It most commonly affects babies between three and six months of age. By the age of two, almost all infants will have been infected with Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) – one of the main culprits causing the condition and up to half of these will have had clinical evidence of bronchiolitis. [1]

This autumn and winter, we will see many babies with bronchiolitis in the ED and the vast majority of these will be assessed and discharged home with safety netting advice. This topic is discussed further in the following blog.

However, there will be some who require hospital admission. This usually encompasses supportive treatment for respiratory compromise with oxygen and monitoring or supplementation of feeds via nasogastric tube. The NICE Guideline for the Management of Bronchiolitis in Children does not recommend the use of any of the following: Antibiotics, hypertonic saline, nebulised adrenaline, salbutamol, ipratropium bromide, montelukast or corticosteroids.

Indicators for admission are:

Background: those who are ex preterm infants, have known cardiac disease, are within the first 3 months of life or have underlying neuromuscular disease or immunodeficiency are considered higher risk and are more likely to require admission.

Presentation: apnoeas, severe respiratory distress and oxygen saturations below 92% in air indicate a need to admit for respiratory support. The recent BIDS study has called into question our current saturation guidance, however until an Emergency Department study is performed, it would be sensible to have 92% as a benchmark. Likewise, once feeding has reduced to half of the usual intake, this is an indication that respiratory compromise is to the degree that these babies will become dehydrated and deteriorate further if this issue is not addressed.

Other factors to consider: putting the clinical presentation into context with the duration of the illness is important, since symptoms will usually peak around day 3-5. Symptoms are also classically worse at night time. It is also vital to establish the parent's perceptions of the illness and their skills and confidence with symptomatic management at home. Therefore, a baby presenting on day 2 of the illness, in the middle of the night, with mild respiratory distress and concerned parents who are reporting they are struggling to cope may be managed differently from an infant on day 4 of the illness whose parents were worried things weren’t getting any better but only has mild respiratory distress and parents are confident at managing at home.

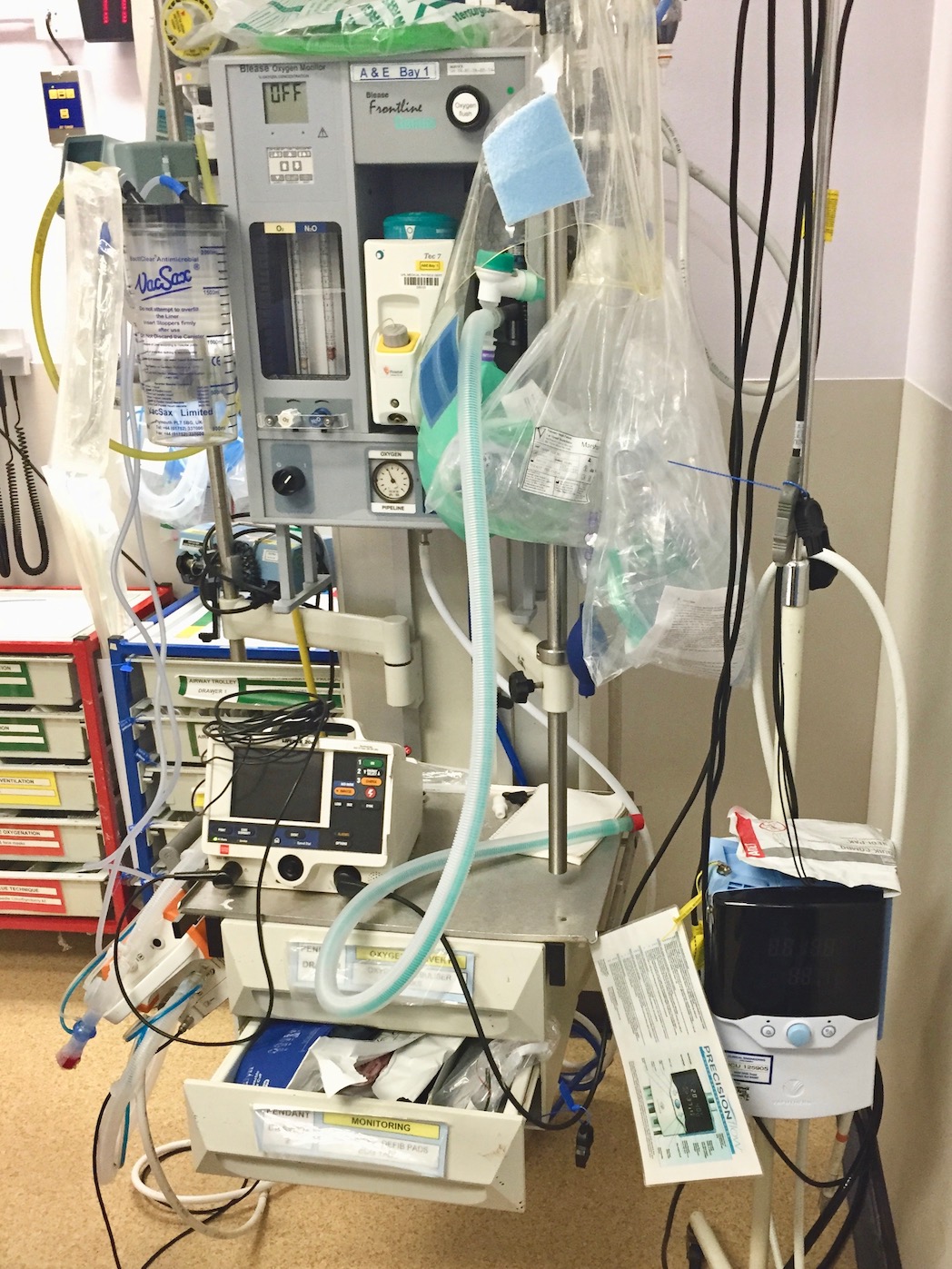

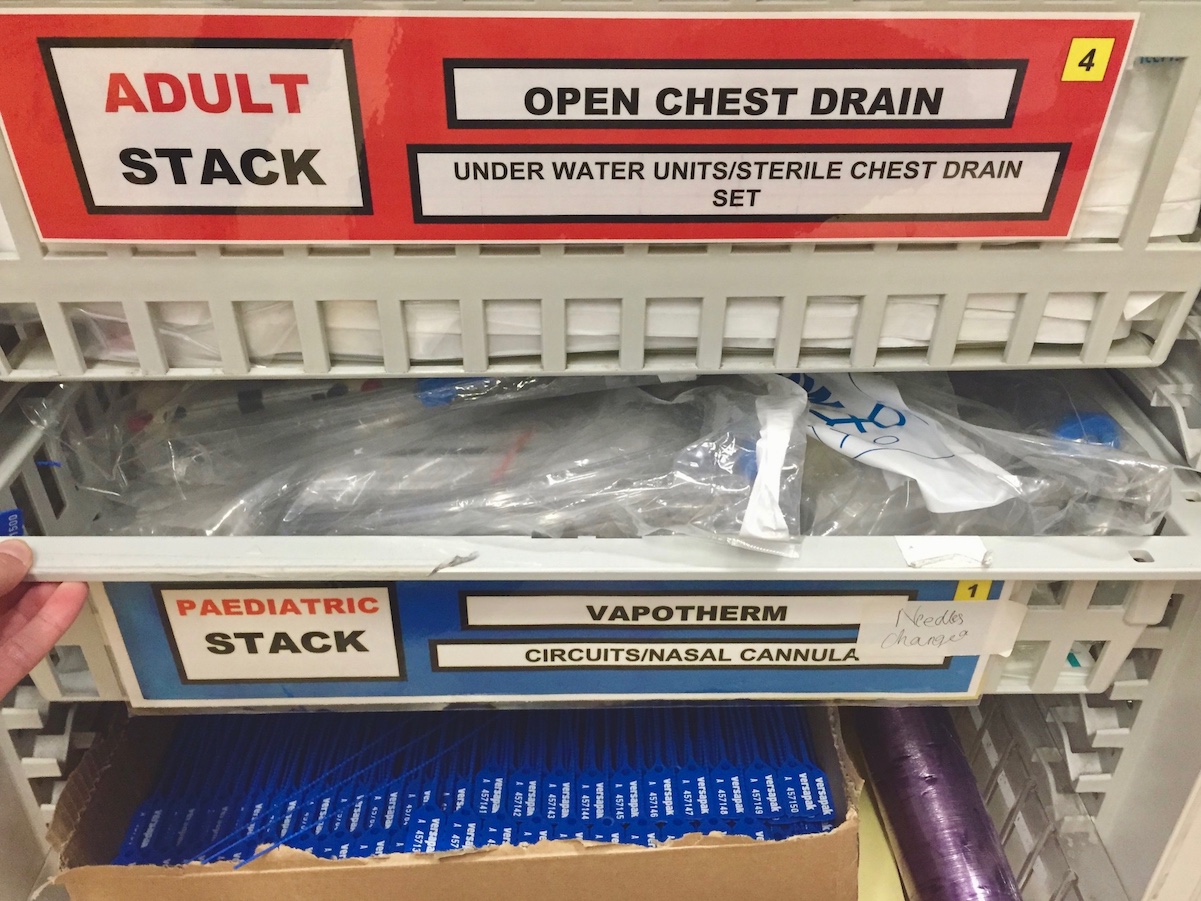

In the first scenario, the baby had severe bronchiolitis which required non-invasive ventilatory support with Vapotherm. This gave our team the opportunity to familiarise themselves with setting up and initiating this treatment in the ED.

Case 2: Why We Simulated?

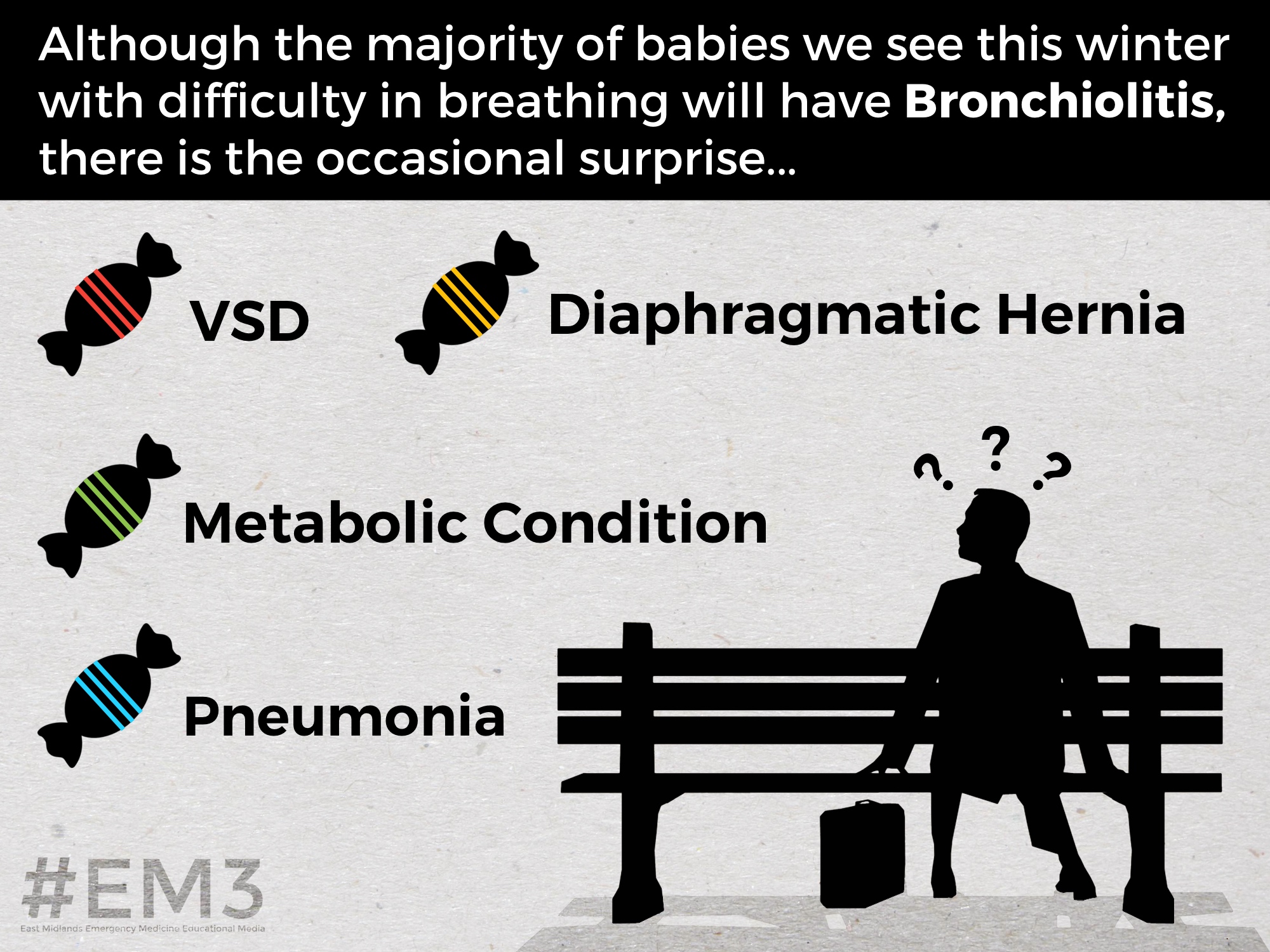

Amongst the babies presenting to the ED with difficulty in breathing, there will also be a minority who have rarer conditions which can ‘slip under the radar’ if we do not keep an eye out for them. Often in such babies, there may be a concurrent bronchiolitis infection but careful history taking and examination may identify that things are more than they initially seem.

Below we have discussed some of these conditions and the useful questions to ask during history taking and signs to look out for on examination:

Sepsis: a fever of 39°C or above is not commonly seen in bronchiolitis and more suggestive of an underlying bacterial sepsis. Consider antenatal, perinatal and postnatal risk factors for sepsis. Group B Streptococcus infection transmitted during labour can cause sepsis as late as 3 months of life. Focal respiratory signs and signs of shock should prompt implementation of the Paediatric Sepsis 6.

Congenital Cardiac Disease: neonates with duct dependent circulations classically (but not always) present unwell in the first few days of life with symptoms of difficulty breathing and poor feeding. Other cardiac conditions such as Ventricular Septal Defects (VSDs) or arrhythmias may present later with a preceding history of poor feeding and sub optimal weight gain. In our scenario, the baby had a large VSD and presented with signs of cardiac failure at 6 weeks of life. These babies can present around this time because the pulmonary vascular resistance falls, meaning left to right shunting across the defect is increased. Signs to look for on examination when considering a cardiac cause for presentation are heart murmurs, absent femorals and signs of congestive cardiac failure – pulmonary oedema, gallop rhythm and hepatomegaly.

Inborn Errors of Metabolism: consider particularly in those babies with a history of vomiting and failure to thrive. Hypogylcaemia may be a feature.

Surgical: congenital diaphragmatic hernias can be missed and present to their local ED with respiratory distress. On auscultation, unilateral absence of breath sounds, sometimes with bowel sounds heard over the lung fields is suggestive, with CXR confirming the diagnosis. Congenital malformations of the lung may also be seen. Those with bowel obstruction may also present with respiratory distress – bilious vomiting, true projectile vomiting or abdominal distension are not features of bronchiolitis and should prompt urgent surgical referral.

Neurological Cause: a history of recurrent choking on feeds and floppiness may be suggestive of an underlying neuromuscular disorder.

While some of the above are relatively rare, the sheer volume of babies presenting with these symptoms means you need to consider alternatives in every case of presumed bronchiolitis you see.

References:

- NHS Choices: Bronchiolitis

Further Reading:

- NICE Guideline: Bronchiolitis in Children: Assessment and Management

- Vapotherm: Vapotherm Pocket Guide

Learning Points

We have a Vapotherm machine in the ED – it is located in the Resus area and the equipment to set it up and instructions to do so are in the Paediatric Vapotherm Stack.

When discharging a patient with bronchiolitis, ensure they are given a Bronchiolitis Information Leaflet which includes advice for when to return to the ED.

Careful assessment of those babies presenting with 'likely bronchiolitis' may reveal the rarer diagnosis.

Positive Feedback

Good skills checking by the team member when allocating tasks.

Despite being unsure of the underlying diagnosis, managed patient safely and appropriately using a step wise approach.