Based at the University Hospitals of Leicester, we serve the educational needs of healthcare practitioners in Acute & Emergency Medicine across the East Midlands, UK

Based at the University Hospitals of Leicester, we serve the educational needs of healthcare practitioners in Acute & Emergency Medicine across the East Midlands, UK

Since the very beginning of medical training, doctors have been expected to teach others. For some, this will involve standing up at an international conference, delivering the nuances of their latest research to an audience of 100’s. However, for the vast majority, it will be delivering a teaching session to peers, juniors, or other members of the multi-disciplinary team (MDT).

Nevertheless, the latter will seem, to many, to be as daunting as the former. Additionally, this expectation doesn’t rest with just doctors, but extends across the MDT.

““...to look upon his offspring in the same footing as my own brothers, and to teach them this Art, if they shall wish to learn it...””

“You’re presenting next week, OK?” has been written with the novice medical teacher in mind, needing a quick rundown on how to deliver a session, and will be of use to any healthcare professional who is just starting on their educators’ journey, irrespective of their profession or intended final career.

To this end, this handbook is designed to furnish you with some basic underpinning knowledge and skills to aid you in delivering your first ‘stand up and speak’ session, whether it’s a regional teaching day, Grand Round, departmental update on new guidelines, or the results of your latest audit.

The handbook is split into three sections;

Preparation: dealing with some educational theory, room layouts and session planning.

Delivery: giving you some tips and advice on how to actually deliver your session.

With a list of further reading and useful resources at the end.

I hope you find this handbook as interesting and enjoyable to read as it was to write, meaning that when ‘the boss’ next says “You’re presenting next week, OK?”, your response will be “OK!”

Preparation for a teaching session doesn’t start as you walk into the room and turn the computer on or open a window. It starts days to weeks before when you’re first asked to deliver a session. This chapter deals with some of the things to consider during the run up to your session, up until your learners enter the room.

A handbook on education and teaching wouldn’t be complete without at least a small section on educational theory. However, this section is intentionally brief, providing an overview of some of the underlying theories which can help to inform your delivery, there is much more information ‘out there’ if you wish to delve deeper, and references are included in the Bibliography. It’s also worth noting that there are many different educational theories, and that whilst each has its merits, each also has it’s criticisms, to this end, there is no one theory that can be considered correct, merely, theories which will resonate more closely with your own practice / beliefs. Three different theories are discussed here, to give you some insights.

Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) was an American psychologist who devised the ‘hierarchy of needs’ (Fig. 1), he believed that obstacles needed to be removed for individuals to achieve their goals. For example, an individual cannot achieve their potential if they are permanently cold or, fearful of persecution. When applying the model to education, you should consider if the basic needs of your learners are met, so as to create the optimum learning environment.

(Fig. 1) Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Although some elements will be beyond your control it is worth considering if there is anything that you can do to influence the lower levels of the hierarchy. For example, when preparing for a session, consider the timing of your session, is it, at the end of a long morning of back-to-back lectures? Or, when you arrive for your session, is the room very hot or very cold? Similarly, during discussions in you session, try to ensure that no individual or group is made to feel devalued by others, through their lack of knowledge/opinion.

VAK (Visual, Auditory, Kinaesthetic), has its origins in the 1920’s and bears a relation to neurolinguistic programming. It focuses on the premise that we primarily learn by seeing, hearing, or doing. As such, it is considered advantageous to, where possible, include delivery techniques that encompass all three styles, thereby involving learners in the process of learning.

““I hear – I forget”

”I see – I remember”

”I do – I understand””

Lectures are by far the most commonly used technique for delivering information, however, they often don’t involve the learner. Mark Twain is often (incorrectly) attributed as having said that a lecture is “the process of transferring the notes of the lecturer, to the notes of the student, without passing through the minds of either.”

Although I wouldn’t wish to cast aspersions on your ability to deliver a lecture, this is certainly an anecdote to be mindful of, is your topic sufficiently engaging to keep your learners interest throughout, or are different delivery techniques required in order to maintain interest? For some, this will equate to group work and handouts/activities, for others, it will be videos or pictures to break up what is an otherwise text heavy presentation. Clearly the variety that can be placed in a session will vary depending on the topic. But it is rare that it is impossible to not use multi-modal techniques to deliver a session.

Constructivism as a learning theory is attributed to Jean Piaget (1896-1980), it focuses on learners either accommodating or assimilating new information based on their prior experiences. Thus, learning takes place through having a reference point on which to base new information.

For example, if I were to ask you to remember “Shampoo, Toothpaste, Milk, Shoes, Coat, Keys” without context you would probably struggle. However, if I were to say it related to my morning routine things would be clearer and you would be better able to remember the list.

It is therefore important to ensure the context of what you are talking about is clear to your learners, this can be established through the learning objectives at the start of the session (see below) otherwise, learners may not understand the relevance of what is being taught.

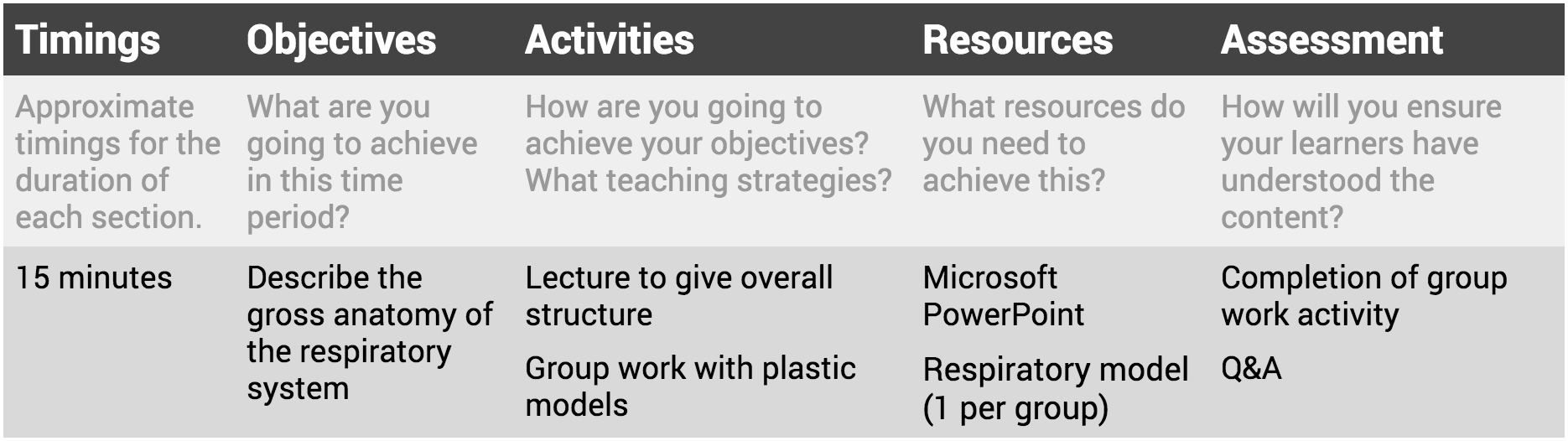

The session plan is the mainstay of a teaching session. A well written session plan will allow anyone with the requisite knowledge to deliver the session how you wanted in your absence. Session plans can run to many pages and will take longer to write than the session will to deliver. However, time spent planning cannot be underemphasised in the delivery of a good session. An example session plan can be found in Appendix 1 – Example session plan.

The first section of the session plan is self-explanatory, we will now take the opportunity to review the other sections, and things to consider as you plan your session.

Who are you teaching and what are you expecting them to know already? On the face of it, delivering a one hour session on ‘Respiratory assessment’ might seem straightforward enough. But, the prior knowledge, and subsequently the objectives and content of your session will vary dramatically based on who you are teaching.

For example, you could be asked to deliver the session to a group of 6 final year medical students, or, you may be asked to deliver the same topic to a 6 first year nursing students, or a mixture of SHO’s and Staff Nurses new to your department.

The prior knowledge of each of these groups will be very different based on their prior experience, so it is always worth considering who you are teaching. If there is mandatory eLearning/pre-course reading prior to the session then this gives you a level playing field. However, if this isn’t the case then it can often be useful to establish early on in the session what participants already know, and similarly, what they hope to learn from your session.

The session objectives/learning outcomes for your session should be SMART. This is a concept that is not unique to education, in fact, any of you who are familiar with the PDP process will have come across SMART objectives.

Your objectives set out what you intend to teach your learners, SMART stands for:

Specific

Measurable

Achievable

Realistic

Time-bound

There are no rules on how many objectives you should set for the session, and a lot of it will depend on the duration and intended content. Often, for medical teaching, it is worth looking at the appropriate postgraduate medical curriculum as issued by the Royal College’s for guidance on what should be covered under that topic. As a rough guide three objectives for a one hour session is generally considered a good benchmark.

The combination of the anticipated prior knowledge of your learners, and your SMART objectives will form the bedrock from which you can plan the rest of your session.

This section should be used to summarise the resources you will need for the session. It will also act as a checklist to ensure you have everything ‘on the day’.

Lastly, and perhaps most crucially, you need to carefully consider how your session will run. Complete a line for each time period you allow, alongside which objective(s) you will address at this stage. Some notes and an example of how to complete this is shown below in (Fig. 2).

(Fig. 2) Example session plan

Where possible, it is best to review the teaching venue prior to the session so that you can gain a feel for how you can best utilise your space to ensure a good learning environment. This also allows you time to consider what activities are realistic given the space you will have, as well as what resources the room has, and what you will need.

The other thing to consider at this stage is the layout of your room, and what will work best for your session, some examples are shown in (Fig 3). Think about the number of participants and activities you may be doing. It’s also a good idea to think about lighting and if this will affect anything you may wish to present on the screen, pay particular attention to colours and font size, as well as windows and the sun.

(Fig. 3) Different room layouts

When used appropriately, resources can enhance the learning achieved within a session immeasurably, and can come in many guises and forms. If you plan to use resources then you need to consider them early, since, even the ‘simple’ handout will take considerable time to prepare. Resources you could consider include:

Handouts of lecture notes/a summary of the session

Equipment to practice with

Flip chart/pens/paper for group activities

Anatomical models

Videos or clips from online websites (but be mindful of trust firewall restrictions and whether a room has speakers)

Information Technology (particularly Microsoft PowerPoint) has certainly become the mainstay of modern educational delivery, however be aware of compatibility issues since the computer in the teaching room may not have the same version that you use. The best solution is to test your presentation works on the PC you will be using before the session, or if you can connect the projector, take your own device.

Ironically perhaps, despite being the thing you will focus on most, this section is notably shorter than the Preparation section. That’s because if a session is well planned, the delivery of it should be straightforward.

Some golden rules are:

Arrive early

Always have a Plan B (and possibly a Plan C)

Don’t be afraid to stray from your session plan (but remember to come back to it)

Watch the clock and finish on time

As mentioned previously (see VAK), whilst PowerPoint has become the mainstay of delivery, it is good to try and not rely on just one technique for delivering your session. In particular consider how you would continue if the projector failed or there was a power cut.

““If you fail to plan, then you are planning to fail.””

Some delivery techniques to consider are:

Group work, e.g. to answer a question/present back to the class; completion of a task/activity

Lecture

Matching exercises

Models, pre-made or asking learners to make them

Question & Answer – facilitated by you

Quiz, either written by you or by learners

Shout out, writing responses on flip-chart or whiteboard

Simulation

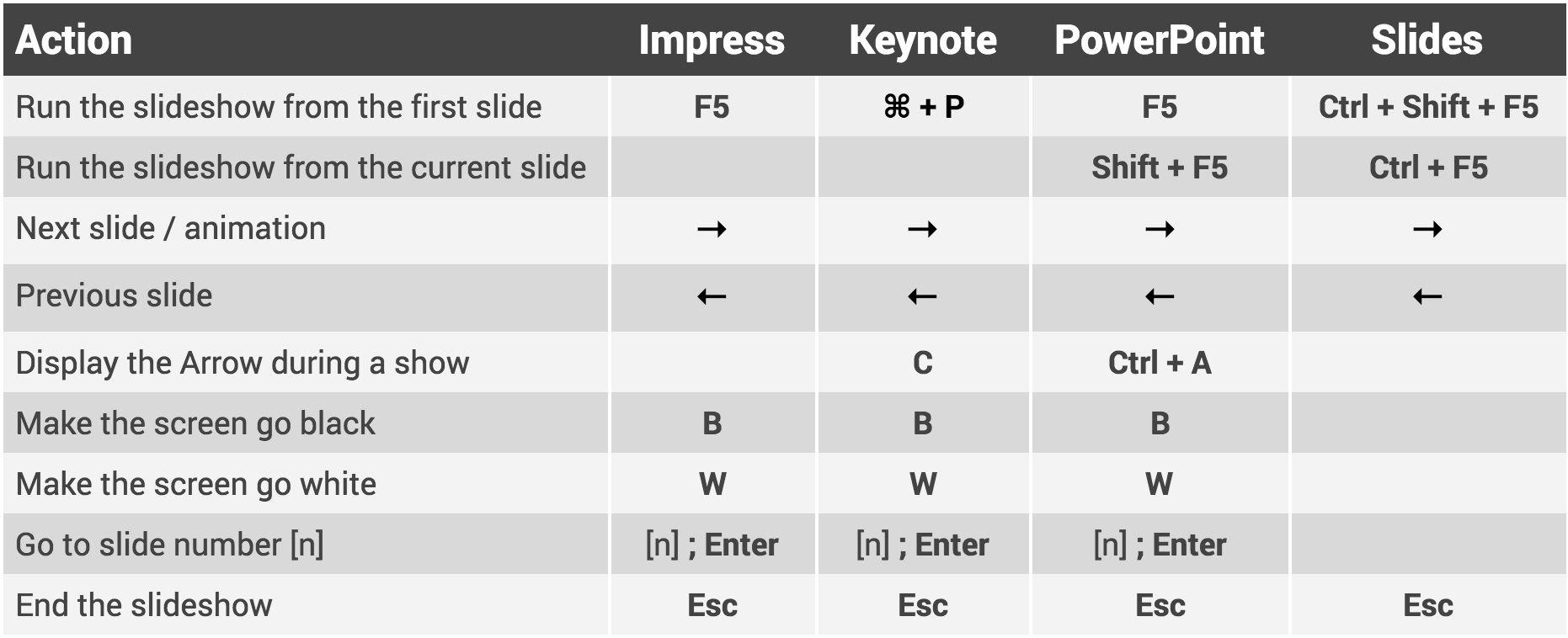

Whilst Microsoft PowerPoint has become the predominant program used to deliver a computer based presentation, it is by no means the only program available for such a purpose. Other examples include Google Slides, Keynote for Mac and OpenOffice’s Impress.

Irrespective of the program being used, some key points are:

Check your presentation works on the intended PC before the session

Do not assume that because it worked at home / in the library / the office it will work in the Seminar / Teaching Room. Frequently you will find different software versions installed across different PC’s

If you are using video / sound, check that the PC has speakers

If using online videos, check that NHS firewall’s don’t block the site

If you are using animation effects, stick to a small number and use them sparingly

Check that fonts / colours can be seen clearly

Rehearse your presentation so that you’re not reading the slide / talking to the screen

Have a ‘Plan B’ in case the PC crashes and won’t load your talk

Lastly, there are a range of useful keyboard shortcuts that can be used to assist you when delivering your presentation. A selection are given below in (Fig. 4).

(Fig. 4) Useful keyboard shortcuts

Whilst not the most educational of phrases to use, ‘aftermath’ quite succinctly sums up some of the thoughts and feelings you’ll probably have after finishing your session. But, it’s important not to rest on your laurels just yet, a lot of what you can learn about delivering a session is best learnt afterwards, with the benefit of hindsight you will learn a lot that will inform your next session.

After every session, you should sit down and reflecting on how it went, some questions to consider are listed in Appendix 2 – Example Post Session Evaluation.

If you have a mentor or nominated supervisor then it’s useful to discuss how your session went with them.

If they were in the audience for your session then why not ask them to complete a teaching observation for you?

An example is given in Appendix 3 – Example Teaching Observation, and many ePortfolio solutions will have their own version as well.

Feedback from your learners is a vital part of understanding how a session has gone. If you are teaching on a longer course then the course convenor will be responsible for organising this. If it’s a standalone session then you are best to discuss this with the person who asked you to present the session.

Most departments have a feedback form that can be used, an example is given in Appendix 4 – Example Learner Feedback Form.

And that’s it! This has been a whistle-stop tour through the preparation, delivery and aftermath of your first teaching session. Hopefully you’ve picked up some useful pointers and things to consider, and will now approach your next teaching session with a bit less trepidation. If you have any feedback then please just drop an email to sjcorry@em3.org.uk.