The Spectrum of Head Injuries

This is a summary of a talk given at Northampton General Hospital on the 11th December 2018 as part of a Pre-hospital & Transfer medicine-themed series. You can find out about future events by following them on Twitter @NGHPTM

The phrase ‘head injury’, to me covers a multitude of different conditions / scenarios and is a catch-all term for a spectrum of disease. At one end we have the true ‘minor head injury’ where you hit your head on a low tree branch / door frame / drip stand and continue with no injuries / consequence. At the other end you have catastrophic life-changing injuries which can, on occasion, be fatal. Within this blog I want to focus on three different entities:

Minor head injury

Concussion

Serious head injury

Statistics

But first, a few statistics taken from NICE:

Head injury is the commonest cause of death and disability in people aged 1-40 years.

Each year, ~1.4 million people attend Emergency Departments in England & Wales with a head injury, which is about 7% of attendances.

33-50% of these are children under 15 years of age.

Around 200,000 people are admitted to hospital / year as a result of a head injury, to put this into a more local context, Northampton has ~500 beds, that’s 400x the capacity of Northampton / year. Leicester Royal Infirmary has ~1000 beds, that’s 200x the capacity / year.

Despite a considerable morbidity, the mortality of patients attending the ED with a head injury is ~0.2%

95% of patients with a head injury present with a normal, or minimally impaired, conscious level (GCS >12).

So, my take home from this is that Head Injury is extremely common and we need to be good at assessing it, but the serious stuff we train most for isn’t that common. That’s not to say we shouldn’t train for serious head injuries, we should, but they’re not as common as you might perceive.

Assessment

Patient assessment should focus on the life threatening issues and follow the usual stepwise <C>AcBCDE approach. If you’ve not seen it then the Glasgow Coma Scale website provides a fascinating background into the GCS score, alongside potential future developments. It’s worth noting the simplified language used on the site, and I think that we sometimes over complicate things.

It’s also important to remember to address any analgesic requirements the patient may have, NICE recommend IV opiates but each case would need to be assessed on its merits. The key thing is to make sure you go back and reassess a patient’s pain and don’t simply assume that a single administration will be sufficient. We also need to think about safeguarding, and decide if there are any concerns in this regard.

Once a holistic assessment of the patient has been completed we can then make a decision about what to do next.

CT Brain

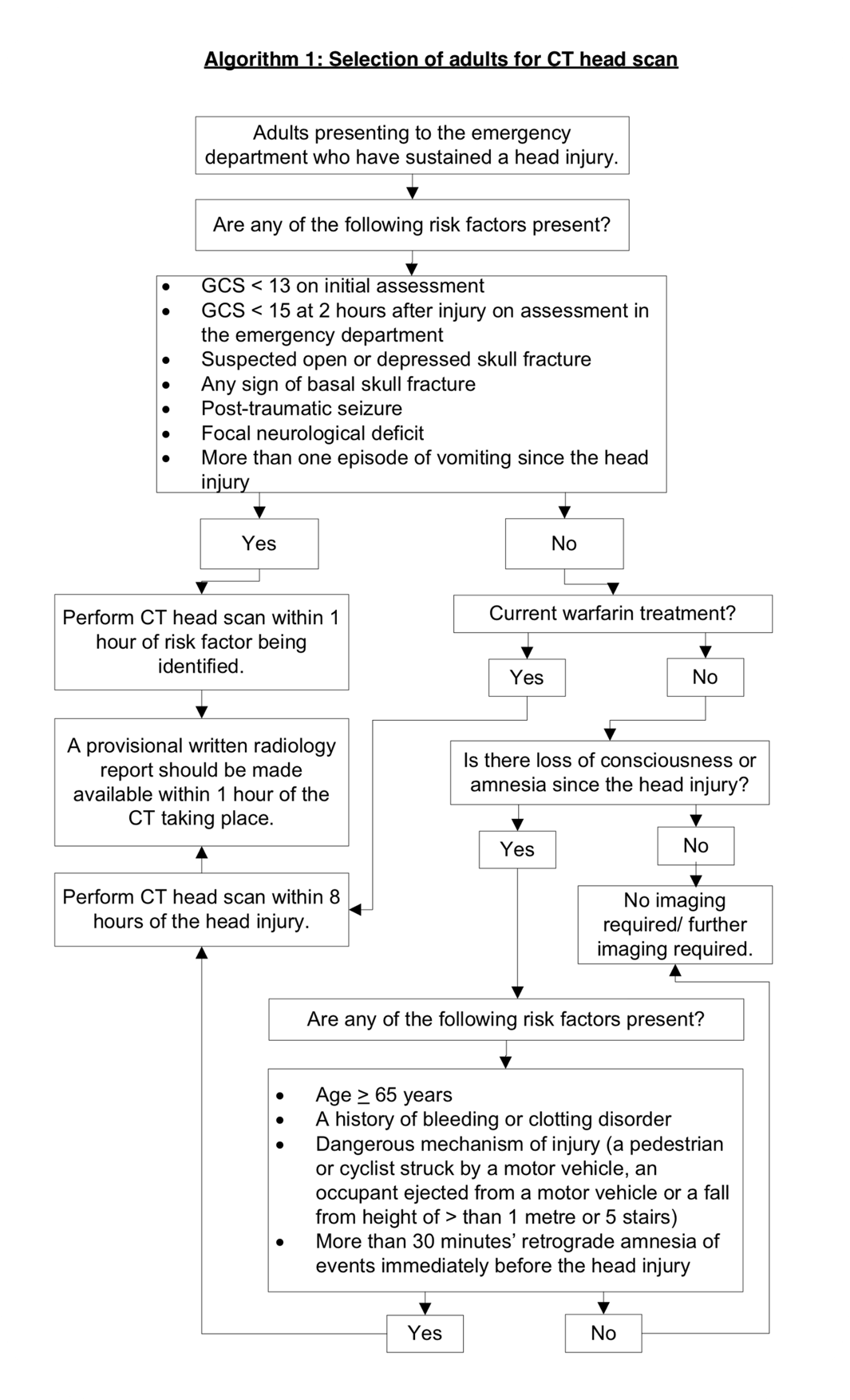

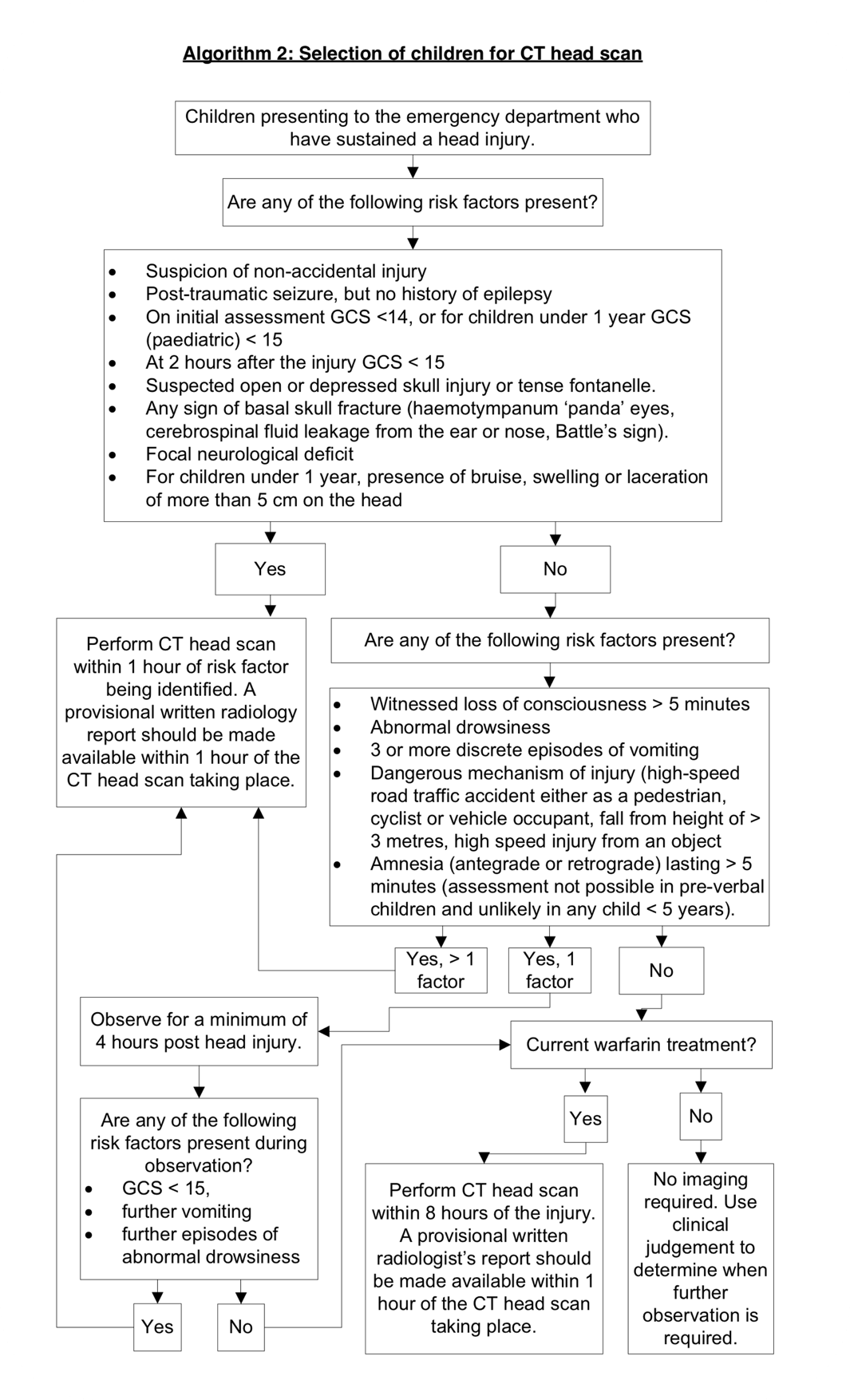

NICE has a very clear algorithm on when we should be thinking about doing a CT Brain / Head on a patient, it’s important to remember that this is an unenhanced (i.e. non-contrast) scan and is designed to look for bleeding / fractures. It won’t pick up things in the same detail as an MRI will, but it’s much quicker and for the purposes of identifying a clinically significant brain injury it will suffice.

It’s worth remembering that a CT Brain isn’t without risk, it’s equivalent to a year’s background radiation, or 100 chest X-rays.

Minor Head Injury

If you go through the guidance for a CT Brain (above) and a patient either doesn’t meet the criteria for one at this point in time, or has a CT performed and it doesn’t show anything, then it is probably safe to discharge them since, in the words of NICE, “The risk of clinically important brain injury to the patient is low enough to warrant transfer to the community”. However, it’s important to note the wording carefully, this isn’t saying ‘no risk’ of a brain injury, and it isn’t saying ‘discharge from healthcare’.

We’re talking about risk and it’s a balance between the risk of missing a clinically important brain injury, and the risk posed by exposure to radiation from the CT (increased risk of fatal cancer with a CT Brain is 1 in 10,000).

Concussion

To me concussion is more of a clinical syndrome than a specific diagnosis. I say this because the symptoms are so varied from person to person, not only in their presentation, but also in their severity and duration. Concussion isn’t like some conditions where there is a very precise definition. Symptoms that people can experience include:

Headache

Dizziness

Nausea or vomiting

Vision disturbance

Sleep disturbance

Change in concentration

Struggling with bright lights / screens

Mood changes

Amnesia

ICD-10 lists concussion as a diagnosis (S06.0 – with many subcategories), but also states that it is a ‘nonspecific term’ characterised by ‘a short loss of normal brain function’.

The symptoms of concussion typically last between days and weeks, and can be quite debilitating. The key feature of treatment is first recognising the condition, and then allowing the brain time to rest and recover by not going straight back to normal activity – in the same manner that if you sprained your ankle you wouldn’t run a marathon the next day, parallels can be drawn with concussion. Various sports bodies have guidance on when competitors can return to sport and it’s usually in a graduated fashion. Headway has some useful information and resources, and the same rules apply with respect to returning to daily activities. It may take days, or it may take weeks so it is important to recognise this and counsel patients and their carers to this effect. NICE recommend that this should be included in discharge advice for patients, alongside how (and when) to seek further help, and advising patients that they shouldn’t be left alone for at least the first 24 hours. Further information can be found in the NICE guideline on Head injuries.

Severe Head Injuries

First, a bit of anatomy. Once the bones of the skull have fused, the skull and cranial cavity become a fixed box. If there is any bleeding into this box, this leads to displacement of the other structures to make room.

Case courtesy of Dr Matt Skalski, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 45683

Where this becomes most troublesome is when there is herniation of the brain from one region to another. Uncal herniation leads to squeezing of the third Cranial nerve which causes the ‘blown pupil’ where it won’t constrict. Whereas tonsillar herniation leads to ‘coning’, that is, compression of the lower brainstem / upper spinal cord – which is the region that contains the cardiac and respiratory centres.

As the bleeding worsens the patient will start to develop what is known as Cushing’s triad, which is hypertension, bradycardia and irregular respirations. This occurs because as intracranial pressure increases it will eventually be higher than the mean arterial pressure, which results in compression of the arterioles and brain ischemia. To combat this the sympathetic nervous system becomes activated, resulting in hypertension in a bid to maintain cerebral perfusion. Baroreceptors in the aortic arch detect this and trigger the vagus nerve resulting in bradycardia. As the process progresses the brainstem becomes compressed resulting in irregular respirations, and then ultimately death.

This all takes place as part of a progressive decline and where time literally does mean brain.

The aims of treatment are to normalise the physiology as much as possible, which means aiming for:

Normoxia

Normocarbia

Normotension

Normoglycaemia

Normothermia

Alongside this any tube ties / collars need to be loose so as not to restrict venous drainage and the head of the bed / stretcher should be elevated to facilitate this. Further, analgesic requirements need to be addressed, and sometimes antiepileptic medications may be given in a prophylactic fashion.

Typically to achieve all this requires intubation and ventilation, the timing of this intervention will depend on the availability of the resources / persons competent to perform the procedure. In the pre-hospital setting, it is sometimes quicker to take a self-ventilating patient to hospital, than it is to wait on scene for a critical care team (or similar) to attend. Clearly this is a case by case issue; but it’s an important consideration to have and requires clear dialogue with control room staff and realistic ETA’s.

Once a CT Head has been performed it may be appropriate to transfer a patient to a neurosurgical theatre (which may or may not be in the same hospital / city / county as the patient) for a decompressive craniotomy, or a watch and wait approach may be more appropriate. Temporising measures that may sometimes be employed are hyperventilation – to lower the CO2, and the use of either 5% (Hypertonic) Saline or Mannitol.

As with a lot of things, the primary injury has occurred, so the focus of management is around ensuring that the injury doesn’t get any worse, and/or minimising the effects of such a process. Key things to highlight are that a single episode of hypotension doubles mortality, and hypoxia can be similarly catastrophic. This relies on doing the basics well, before more advanced interventions can be planned / employed.

For a final link, the NHS England clinical guidance for major incidents and mass casualty events has a good section on neurological trauma.